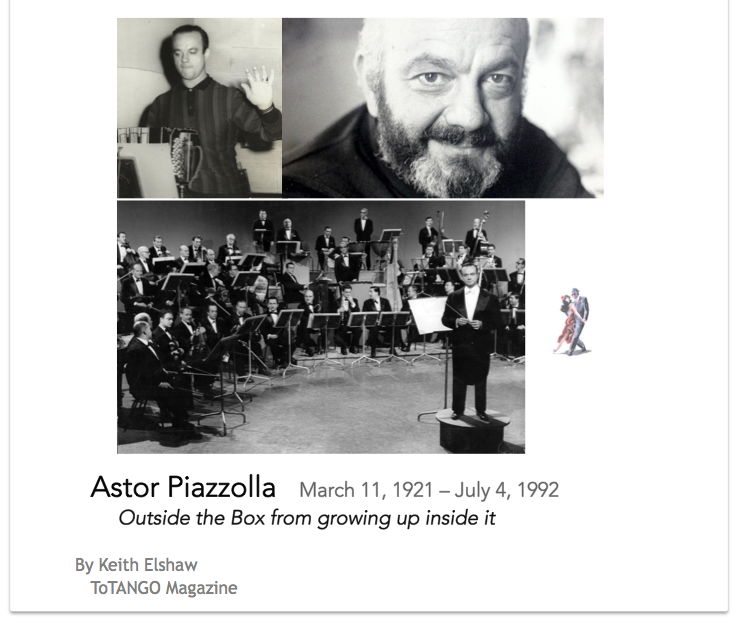

"I still can't believe that some pseudocritics continue to accuse me of having murdered tango. They have it backward. They should look at me as the saviour of tango. I performed plastic surgery on it." - Astor Piazzolla

"Piazzolla's tango has the eyes, the nose and the mouth of it's grandfather, the tango. The rest is Piazzolla."

- Ernesto Sábato

"Piazzolla forced us to study - all of us." - Osvaldo Pugliese

Watching Astor at work, listening to his expression of the divine, you wouldn't naturally have pictured a fighter (the other kids called him "Lefty" because he packed a whallop); a scrambler on the mean streets of 1920's New York, his family having moved there from Mar del Plata. Among his boyhood friends: a few mafiosi and the future world heavy-weight boxing champion Jake Lamotta, "The Raging Bull" of Scorcese's biopic.

Astor was the outsider. He was smallish. He had to prove himself to himself and the world. One leg was shorter than the other - so he took tap-dance lessons and played baseball to show that he wasn't "different." He fought. He connived. He survived. And he taught himself to play the bandoneón.

"My first bandoneón was a gift from my father when I was eight years old. He brought it covered in a box, and I got very happy because I thought it was the roller skates I had asked for so many times. It was a letdown because instead of a pair of skates, I found an artifact I had never seen before in my life. Dad sat down, set it on my legs, and told me, 'Astor, this is the instrument of tango. I want you to learn it.'

My first reaction was anger. Tango was that music he listened to almost every night after coming home from work from his barber shop. I didn't like it."

Fast-forward four years. One day Astor's uncle rushed in the door and said, Astor has to come with me down to a film studio! Carlos Gardel is making a movie and they need a bandoneón player!

Astor initially had no idea who Gardel was.

The book Astor Piazzola - A Memoir recounts the story of Astor bringing Gardel home for dinner and of other times spent with the legend while he lived and filmed in New York.

Astor would sneak out at night to see Cab Calloway in Harlem. He also went down to Macy's with Carlos Gardel, guiding the eternal icon of Argentine Tango around New York in the daytime and being his bandoneónist for a few months. Astor's parents wouldn't let the 12-year-old go on tour with Carlitos ... the only reason he wasn't on that fateful flight out of Medellin that took Gardel forever.

Never did Astor later try to capitalize on the association, as doubtless others might have.

The first music Piazzolla played on the bandoneon was Bach. He felt more afinity for Gershwin and Stravinsky than for Villoldo or Canaro ... until as a teenager, now living back in Mar del Plata, he encountered in person and became influenced by Elvino Vardaro and Miguel Caló; then Troilo. (And he forever after spoke of his admiration for Alfredo Gobbi).

That he was a complicated, angry man and isolated all his life is no revelation when you read his memoir; neither is it surprising to see his ego, sensitivity and emotion revealed. All of that is obvious in his music.

But it is a sweet relief to take away from the book the feeling that if you knew him personally, you would probably love him as much as you do his music. And in that loving, you would find it in your heart to overlook his maddening qualities, as one does with a good friend. One might just have liked to keep the relationship a little distant, that's all.

A former business manager is quoted as saying, "Who is Piazzolla? Onstage he is God; offstage a son of a bitch."

I liked this little book a lot. I am the kind of person that likes to have a tome full of details to plow through (and the time for the plowing) - but no matter what is written about Piazzolla in the future, this volume is likely to stand with any as the definitive written portrait of the man.

The author, Natalio Gorin, had the access of a friend, the ear of a knowledgable fan and the eye of a journalist. He knew what should be revealed and found a way to do it. Piazzolla was taken by passing from the project before its completion, so Groin had to finish it alone. This he did using portions of letters and his own writing, together with contributions from other Piazzolla friends.

We follow Piazzolla from his beginnings as a poor boy in depression-era New York, to side-man then arranger in the Golden Age of Tango in Baires, to Rome and Paris in the era of jazz, jet travel, concerts, film and rock stars. The reader listens-in on Astor talking to a trusted friend about his music, his muse, his relationships: with his bandoneón, his musicians, teachers, influences, critics, friends and lovers. And the way he was, as a person and musician, from his own point of view.

"I talk to the bandoneóns.That's why I swear that at one time El Gordo's fueye (Troilo's bandoneón) cried, 'Ay!' I think I hurt it. Maybe I banged a button with my finger. I play with violence; my bandoneón must sing and scream. I can't conceive of pastel tones in tango. I speak to him (the bandoneón) so he doesn't stand me up in the middle of a concert. Sometimes I beat him up."

Reading this Memoir, that most beautiful of aids to understanding, context, is drawn. You learn about his views on his work and recordings. You see the life of the Tango musician through his eyes; hear his thoughts about those who went before and who came after. He is candid about his recordings and his business dealings. He shares his triumphant feelings and his regrets. He owns up to his wicked practical jokes. He talks about the most inspired moments in his life, the happiest, lowest and the most touching. These insights make one feel closer to the music.

My dear friend and former wife, dancer Cristina Rego, was in the Copes company for over 30 years. From her I got more impressions of Astor as he was with his close friends and fellow performers.

They were working in Puerto Rico when the devastating news came to Astor that his beloved father had died. Astor put down the phone and went to his room next door; sat down with his bandoneón and composed his signature Adio Nonino. The next time you hear that song, you can visualize Nonino bringing home that mystery box to the 8-year-old Astor and hear in the notes the tears, love and immeasurable gratitude pouring out of Astor that - thanks to god - there weren't roller skates inside.

Even those who love tango tango but don't have much affection for Piazzolla would, I'm sure, enjoy reading the passages about his life in the Troilo Orquesta from 1939-45. They had a deep and abiding love for each other that is one of the most important relationships in the tango world.

After leaving Troilo's Orquesta, Piazzolla led a band for for a time with Fiorentino his singer, and worked as an arranger for Troilo, Fresedo, Basso and Francini-Pontier (who recorded first his composition Lo Que Vendra).

Without: 1. Gardel's early tutelage 2. Troilo's belief and sponsorship; 3. Nadia Boulanger's inspirational guidance; 4. Copes' sponsorship and support after his time in Paris when he didn't have any income or idea of what to do next, we never would have the experience of the genius of Astor Piazzolla.

It is interesting that, even while speaking Spanish, Astor often used an English word to find the way to say what he wanted to. Not only did this make the translator's job easier, it leads to more trust in the reader that things didn't get "lost" in the translation. This is the best (most comfortable) translation work from Spanish about tango I have ever read.

Here is a sample of Gorin's first-person writings:

"In Piazzolla's home in Punta del Este in March 1990 during a pause in our taping, listening to the piece (La camorra), I asked Astor about a noise that comes out of his throat (his soul?). The cry is a rare mix of fatigue and ecstacy that can be heard clearly in the middle of a dazzling jam. He answered me with a characteristic line that reflected his pride and his joy for having reached such a musical level with the Quintet. 'I left my lungs in that recording,' he said. That was Piazzolla. That's the way he was until August 4, 1990."

And, Gorin reports, it is indeed true that Piazzolla said - not just a few times to his band behind closed doors - "Screw the people and let's play what we musicians like."

This book is no apologia for the scrappy kid who loved to let fly with that amazing left-hook of his.

Included are short remembrances by Horacio Ferrar (collaborator), Gary Burton, Atilio Talí (last manager), Anahí Carfi (last violinist to tour with Astor), and two of his favorite bandoneónistas: Leopoldo Federico and Roberto Di Fillipo.

Gary Burton: "As a jazz musician, I tend to compare Astor to a combination of Duke Ellington and Miles Davis ..."

Being an unabashed romantic, I have always had the wistful dream of being able to somehow be transported in time so that I could live for a while in Buenos Aires in, say, 1940. Each night would find me in a club with a different orquesta to dance to and have dinner with after. Caló, Pugliese, D'Arienzo, Di Sarli, Gobbi, Canaro, Tanturi, D'Agostino ... and Troilo. Sweet, generous El Gordo. And there on the bandstand, exchanging knowing, intimate glances with the great man, is the fresh-faced nineteen-year-old hell-raiser and upstart arranger, Astor Piazzolla. This book takes you a believable (if only fleeting) step closer to seeing yourself back there with them in your dreams.

While reading this book, with Astor's recordings playing in the room, I was transported. (Isn't that why we love books? And music?)

My thanks to the Publishers for their kind permission to quote passages from the book on ToTANGO and for circulating this article to promote it.

Astor Piazzolla - A Memoir - by Natalio Gorin, Translated, annotated and expanded by Fernando Gonzalez AMADEUS PRESS ISBN 1-57467-067-0

Famous Footage: Astor Piazzolla Live at the Montreal Jazz Festival Unbelievably great playing by his last quinteto

See also:

Astor studies with the great Nadia Boulanger