The modern tango scene was born in controversy and it has generated many stories - real and imagined - that continue to emerge around this controversy. It's a fascinating theme to explore.

Personally, I am not only interested in the stories of all the tango greats, but by the reasons they did what they did and then importantly by what resulted from their artistic success.

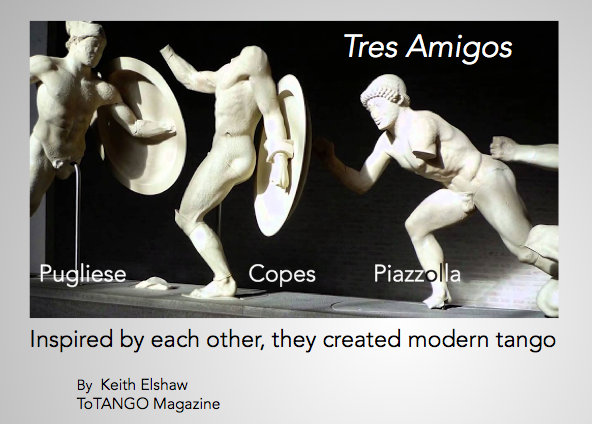

In this connection, I would point to the role of The 3 Amigos above - and to the historical moment when they created and explored a new world; and to how they depended on each other for support.

Seventy three years ago - the earthquake

To understand the tango world of 2017, we must zoom in on the moment of a literal earthquake that happened 73 years ago.

No one knew it, but the death knell for the Golden Age of tango was rung at a fundraising gala for earthquake victims in Luna Park on January 22, 1944.

That evening, Secretary of Labour Juan Perón met and fell under the spell of film actress Eva Duarte.

Yes, to understand the modern tango dilemma we do have to talk about them. The actress and Perón are actually central to understanding how we got here today.

For Evita appropriated tango's profound imagery to wage her war of conquest. Together she and Perón raised tango culture up to official high prominence, only for it then to be smashed in their fall just eight years later.

Ia a nutshell, it was obvious to Eva that Perón needed a make-over if they were going to get to the top. So she put him through the school of how to assume the pose of Carlos Gardel. The Olympian god of Argentine culture had been gone for almost 15 years; the timing was perfect to redo the dull career army officer in Gardel's suave, heroic image - even if the uniform had to stay. And so the air of tango romance became the soft-branding imprint of their rise and reign at Casa Rosada.

Argentina's version of the Camelot myth was launched when Peron became President in June, '46. Eva had learned a lot about the magic of image and P.R. in the film business. She glorified high-society tango in her short reign knowing that was an irresistible stroke to the nation's ego. But then she died in 1952 and Juan fell in 1955.

His fall brought a wave of repression and it aimed at extinguishing all signs of their era and their brand. In crude terms, tango must be killed and order restored. No milongas, no nightlife. No good orquestas on the radio and a bare few can make records regularly. Real tango was forced underground, onto life-support. Uninspiring government-approved tango replaced it on records and radio.

Q: If they hadn't used it as branding tool, would tango have suffered so apocolyptically when they were gone? Hmm. Probably not.

Under the surface

Yet through this time something was brewing under the surface. A successful 47-year-old composer, pianist and orquesta leader felt stirrings inside that he had to pursue. In 1946, Oswaldo Pugliese came out with a tango that would come to change his life and tango's - that song was the first draft of "La Yumba".

By 1952 with the arrival of revolutionary new audio recording, manufacturing and playback equipment not only in record companies, but in radio stations and homes, sound recording and reproduction had miraculously jumped way up in quality.

This was Osvaldo's moment. What he wanted to say could be captured in its nuances with the new technology. Those new ideas of his were not "drafts" after-all; he recorded La Yumba again virtually exactly as he had 6 years previously. This time, sounding so much bigger, clearer, richer, it felt like the eruption of another earthquake. Where it erupted was actually inside the heads and hearts of certain aspirant artists lurking in the underground tango scene of Buenos Aires. And in one in particular who also was struggling to formulate grand new ideas never expressed, never imagined before.

Juan Carlos Copes seemed to know what he was going to do before he could actually do any of it.

In 1952 he was 21 and had decided his parents would just have to get over their great disappointment in him. He was NOT going to be a plumber as they wished. He was going to be a tango dancer! And not just a dancer - he was going to be the next Gene Kelly and be famous around the world!Really, this was madness. How can you be a tango dancer when the tango is obviously dying? How are you going to earn a living? And he couldn't dance anything really, let alone tango - except in his mind.

His mind's eye indeed saw his path forward. That girl Ñiata Rego from the milonga; he would have her as his dance partner and then he could get really good really fast.

Copes had a "simple" concept: choreograph tango for stage performance.

I am going to be just like Gene Kelly. He is dancing on Broadway, on the big screen - even on this new thing called TV!

He put on Pugliese records and invented movements to go with this new music and before you could say La Yumba he had become a "professional" tango dancer with Ñiata, his dream partner, and he was making things happen. He got himself on tiny stages here and there and he made ends meet.

But then ...

Ñiata's wedding day was approaching and her fiancé lowered the boom: no more tango dancing for you!

Undeterred, Juan sidled up to her 14-year-old sister, Maria Nieves Rego. Come with me. We're going to be famous. They snuck her into clubs, did his idea of a show and rushed her out before anyone could think to ask how old she was. And they took off. All of it out of his imagination and their incredible innate talent and hard work.

Interestingly, Copes and Nieves' grand "official" public crowning as the new international stars of the tango firmament took place in Luna Park again - before thousands of awed people in 1959. An interesting aside: introduced - in his last show ever - by great godfather of tango, Francisco Canaro, conducting his exquisite orquesta as they danced.

History now knows Copes y Nieves as the most famous tango dancers who have ever lived.

Keeping tango alive in troubled times

Copes and Nieves would become cultural icons in their homeland - above restrictions of mere mortals such as curfews - and stars of Las Vegas, Broadway and premier stages around the world. They performed on the famous Ed Sullivan TV show at least once every year.

Copes' touring became a tango industry for Argentina employing artists and crafts people in all the parts of theatrical production. He took in fresh young talent and molded them into stars. He kept fabulous older dancers and musicians working and chuffed with dignity. Continuously for more than 40 years. When I first met Juan in 1989 in Toronto, he brought 38 Argentino cast and crew, dependant on him in Canada for 5 months.

This wasn't social tango, but it kept tango alive on that new, professional level he had willed into being. It brought floods of people in to take classes and join the nascent tango scene in every city they visited. It did indeed give tango a future: it has been said that every tango dancer outside of Argentina around the world is a descendant of Juan and Maria.

Juan Copes loved the great tango orquestas and paid tribute to the originators of the tango in every step he took. But Pugliese's music had a depth of expression, the vivid sound of a new world, and passionate, climactic show-stoppers. It was a marriage made in heaven. Copes' artistry was boosted by exceptional, new music to go along with the glorious traditional tangos - abroad.

But in Argentina, social tango was underground - in private family gatherings and hidden, private clubs. The junta had repressed it, Pugliese was in and out of jail for loudly fighting for the rights of the common person. It was a troubled time.

Maria Nieves described to me the surreal scenes at their shows in Argentina which people had paid handsomely to attend. "We look out and see military on the right, mafia on the left, the people in the middle. Pugliese in jail while beautiful Pugliese music is coming from our stage."

And then, Piazzolla

From working his way up in the great Troilo orquesta in his twenties as musician, arranger and composer (Troilo was brave!), to providing the live musical impetus Copes needed to wow audiences everywhere, to composing songs the inestimable Pugliese delighted in putting in his own catalogue of recordings, Astor was to Copes, "a visionary."

Astor was Juan's orquesta leader for 3 years - the best possible way for him to stay alive financially, travel the world to make contacts and find an audience for his new compositions.

It was Juan who brought Astor's songs to the world, and it happened in tango because on returns home Pugliese (or Troilo) would be his backing orquesta. Juan handed Osvaldo the scores for such new songs as Adios Noñino, Verano Porteño and Libertango. Astor was receiving support and exposure he had earned, but which could have come in such measure from nowhere else.

The fascinating Astor Piazzolla story

Living where tectonic plates collide is dangerous to mankind, but - that's exactly where cultures from Mesopotamia to Silicon Valley have thrived.

And it seems written that the tango tango / modern tango fault-line sides will struggle for a comfortable embrace any time the modern tango genesis story, conceived in a vacuum of no social dancing, is forgotten.

Editorial wisdom: Sandra Thibaudeau